The Forger – Our family’s secret savior?

March 18, 2010 at 8:27 pm | Posted in -- POLAND, Family History, Holocaust, Jews, Joseph Rubinsky | Leave a comment I don’t have a photo of Joseph Rubinsky, but here’s something better: a sample of his work. What you see is a 1926 American entrance visa, a rare gem at a time when millions of refugees from war-scarred Eastern Europe were still trying to reach the US but were blocked by newly-imposed immigration quotas. This visa was worth a fortune on the black market. It was a beautiful, profitable, elegant fraud. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of illegals, mostlty Polish and Russian Jews, fooled the Ellis Island inspectors with these Rubinsky forgeries between 1922 and 1926 before officials finally caught on.

I don’t have a photo of Joseph Rubinsky, but here’s something better: a sample of his work. What you see is a 1926 American entrance visa, a rare gem at a time when millions of refugees from war-scarred Eastern Europe were still trying to reach the US but were blocked by newly-imposed immigration quotas. This visa was worth a fortune on the black market. It was a beautiful, profitable, elegant fraud. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of illegals, mostlty Polish and Russian Jews, fooled the Ellis Island inspectors with these Rubinsky forgeries between 1922 and 1926 before officials finally caught on.

Beating the immigration rules made Rubinsky a criminal. Police arrested him at least four times during the 1920s in Poland, Germany, and France. But each time, he managed to buy or connive his way out of prison and went immediately back to business.

His final known arrest came in July 1926 in Danzig, just a few days after German police had seized six people in Berlin traveling with forged Polish passports and forged German and American visas — Rubinsky originals. By then, Rubinsky, just 35 years old, had had enough. He bought himself out of jail one last time, then disappeared, slipping back into the USA under a false name then vanishing into Canada. Not even J. Edgar Hoover could find him.

A few months ago, digging through old diplomatic files at the US national archives while trying to reconstruct the story of how my own grandparents came from Poland to America in the 1920s, I happened to come across the original 1926 cable from US diplomats in Berlin reporting on the arrests there, and was more-than-slightly surprised at seeing the names of the six people arrested for carrying the fake Rubinsky documents. One was listed as Hinda Bronfeld — my future mother, then just 14 years old — and two others as her siblings, my future uncle and aunt.

Was the forger Rubinsky the secret hero who saved our family from the holocaust by sneaking us out of Eastern Europe before the Nazi disaster? Or were we victims of a gigantic hoax?

No one in my family had every heard such a story, and all that generation — our parents, uncles, aunts, and grandparents who made the immigrant journey in the 1920s — had died years ago. Had the Berlin arrest been a secret they carried to the grave? A case of identity theft? Or something else? Now, for the last six months, I have been trying to figure out what went on.

So far, all we know about Rubinsky comes from an investigative file kept by the US Immigration Bureau, plus a letter from the FBI and a few related cables from US diplomats. We know that Rubinsky was short and skinny, stood five feet three inches tall and weighted 112 pounds with brown hair and brown eyes. He spoke Russian, Polish, Yiddish, French, German, and perhaps a few other languages along with English, born in Kiev, raised in New York City, a fast talker with good hands. He had a wife named Ida who stayed behind in New York while he traveled the world, and two daughters named Henrietta and Dora. He and his gang — police say he had at least seven accomplices — operated out of two crowded apartments, one in Warsaw and the other in Danzig.

What made Joseph Rubinsky leave his home, cross the ocean, and become an underworld smuggler? Was it just the money? What mental demons could have been driving him to face repeated arrest and prison, deal with the lowest swindlers, extort the last pennies (zlotys) from destitute refugees? Did he glory in his own brilliance as a swindler, a forger-artiste, a street operator? Did he see himself a hero, a profiteer, a gambler?

I aim to find out more about this Joseph Rubinsky and the underworld of 1920s forgers and smugglers who, in their own gray, selfish, compromized way, apparently saved many many lives. Is he hero or villain? Stay tuned.

var _gaq = _gaq [];

_gaq.push([‘_setAccount’, ‘UA-1573495-6’]);

_gaq.push([‘_trackPageview’]);

(function() {

var ga = document.createElement(‘script’); ga.type = ‘text/javascript’; ga.async = true;

ga.src = (‘https:’ == document.location.protocol ? ‘https://ssl’ : ‘http://www’) + ‘.google-analytics.com/ga.js’;

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s);

})();

var gaJsHost = ((“https:” == document.location.protocol) ? “https://ssl.” : “http://www.”);

document.write(unescape(“%3Cscript src='” + gaJsHost + “google-analytics.com/ga.js’ type=’text/javascript’%3E%3C/script%3E”));

try {

var pageTracker = _gat._getTracker(“UA-1573495-6”);

pageTracker._trackPageview();

} catch(err) {}

var _gaq = _gaq [];

_gaq.push([‘_setAccount’, ‘UA-1573495-6’]);

_gaq.push([‘_trackPageview’]);

(function() {

var ga = document.createElement(‘script’); ga.type = ‘text/javascript’; ga.async = true;

ga.src = (‘https:’ == document.location.protocol ? ‘https://ssl’ : ‘http://www’) + ‘.google-analytics.com/ga.js’;

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s);

})();

Welcome to America, 1920

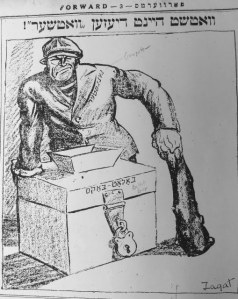

March 9, 2010 at 8:57 pm | Posted in Deer Taag, Dutch Schultz, Family History, Jewish Daily Forward, Legs Diamond, Luckuy Luciano, Murder Incorporated, Palmer Raids, Yiddish cartoons | Leave a comment What a country! In America, gangsters controlled the ballot box. Don’t take my word for it. Here’s the featured cartoon in the Jewish Daily Forward from Election Day, November 2, 1920. Republican Warren Harding beat Democrat James Cox that day, but the Forward rejected both of them. It’s candidate was the Socialist, Eugene V. Debs, running his campaign from prison, serving a term for wartime sedition. Debs would get over a million votes.

What a country! In America, gangsters controlled the ballot box. Don’t take my word for it. Here’s the featured cartoon in the Jewish Daily Forward from Election Day, November 2, 1920. Republican Warren Harding beat Democrat James Cox that day, but the Forward rejected both of them. It’s candidate was the Socialist, Eugene V. Debs, running his campaign from prison, serving a term for wartime sedition. Debs would get over a million votes.

November 1920 was also the month that my grandfather landed at Ellis Island, having fled Eastern Europe a step ahead of the law (see prior posts). Having left wife and children behind, he found himself rootless and moniless, stranded in the biggest, freest city on earth — a far cry from backwoods Poland. It would take six years to bring over the rest of the family.

It wasn’t just politics that must have seemed strange to him. Here’s a cartoon that month from another Yiddish Daily, The Day (Deer Taag). Here, the corrupt goon is the fat, rich landlord squeezing pennies from his impovished slum tenants.

It wasn’t just politics that must have seemed strange to him. Here’s a cartoon that month from another Yiddish Daily, The Day (Deer Taag). Here, the corrupt goon is the fat, rich landlord squeezing pennies from his impovished slum tenants.

Want more goons? Try the police. Earlier in 1920, New York coppers backed by Justice Department agents had rounded up over 5,000 recent immigrants in the notorious Palmer Raids, holding them for weeks on vague charges of disloyalty, deporting almost a thousand, then freeing the rest. “Third degree” tactics were normal back then; “civil liberties” was mostly still just a fancy word on college campuses.

Did I mention organized crime? Let’s see. There were the gangs under Lucky Luciano, Dutch Schultz, and Legs Diamond, not to mention Albert Anastasio and Murder Incorporated over in Brooklyn. And they were just the celebrities.

Want to cross the street? Try walking through this: Driving around New York.

We have built a ridiculously nostalgic image of life for immigrants reaching America in the early Twentieth Century. Don’t be fooled. It was hard, raw, painful, and unforgiving: the back- breaking strain of sweatshop labor, the squalor of tenements, and disdain of the native born. By 1921, “old” Americans grew so hostile against newcomers that they imposed the most restrictive peacetime immigration quotas in history.

Psychologists use a phrase to describe how people can take a painful experience and color their own memory to justify it by turning it into something glorious and honorable — cognitive dissonance. That’s the American immigrant experience.

Pilsudski

March 5, 2010 at 10:35 pm | Posted in -- POLAND, Family History, gerrer rabbi, Henry Morgenthau, Jozef Pilsudski, Lvov, pinsk, polish partition | Leave a comment

But the pogroms…

What they didn’t know what that just a few years later, in 1939, the Russians would come back, this time allied with Nazi Germany, and over 95 percent of the Jewish people who stayed behind would be murdered.

var _gaq = _gaq || [];

_gaq.push([‘_setAccount’, ‘UA-1573495-6’]);

_gaq.push([‘_trackPageview’]);

(function() {

var ga = document.createElement(‘script’); ga.type = ‘text/javascript’; ga.async = true;

ga.src = (‘https:’ == document.location.protocol ? ‘https://ssl’ : ‘http://www’) + ‘.google-analytics.com/ga.js’;

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s);

})();

var _gaq = _gaq || [];

_gaq.push([‘_setAccount’, ‘UA-1573495-6’]);

_gaq.push([‘_trackPageview’]);

(function() {

var ga = document.createElement(‘script’); ga.type = ‘text/javascript’; ga.async = true;

ga.src = (‘https:’ == document.location.protocol ? ‘https://ssl’ : ‘http://www’) + ‘.google-analytics.com/ga.js’;

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(ga, s);

})();

Trotsky

March 5, 2010 at 7:46 pm | Posted in Battle of Warsaw, Family History, Jozef Pilsudski, Miracle on the Vistula, Trotsky | Leave a comment In digging into the story of my grandparents and their flight from Eastern Europe in the 1920s, I was surprised to learn that two giants of the age held our fate dangling at whim at one key point. One was Polish leader Jozef Pilsudski, whom I’ll talk about next time. The other was Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known by his revolutionary nom du guerre, Leon Trotsky.

In digging into the story of my grandparents and their flight from Eastern Europe in the 1920s, I was surprised to learn that two giants of the age held our fate dangling at whim at one key point. One was Polish leader Jozef Pilsudski, whom I’ll talk about next time. The other was Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known by his revolutionary nom du guerre, Leon Trotsky.

What a strange man, Trotsky, a zealot among zealots. Look at him in this 1919 photo, strutting about as Commissar of War in the new post-1917 Bolshevik Russia, rousing his Red Army troops. He spoke in spell-binding sentences, brilliant as a writer, tactician, or theorist. People loved him, hated him, and feared him. Born and raised Jewish, he rejected it as a young man as bourgeois fluff. “I am a Social Democreat and only that!” he insisted when asked.

In 1920, Trotsky was still neck deep defending Red Russia in a gruesome civil war, pitting the new Leninist regime against not only White Russian reactionaries but also an international expeditionary army from Britian, France, Japan, America, and other countries. Still, that spring, on orders from Moscow (Trotsky fought the idea at first), he launched a full-scale invasion of the newly-created country of Poland — what he called a land of “oppression and repression under a cloak of patriotic phraseology and heroic braggadocio.” The plan was to spread revolution both to Poland and through Poland, reaching German and the west.

By summer, Trotsky’s Red Army had knocked Poland’s defenders on their backs, sending them into heavy retreat. Soon they were closing in on Warsaw itself for a knockout blow.

This is the war that my grandfather, Rubin Mendel Bronnfeld, then a 29 year-old father of five young children living in a tiny village shtetl called Zawichost, was asked to fight. That spring, the Polish army, desperate for soldiers, expanded military conscription to include 30 year-olds — even Jews like him. By this point, my grandfather had already seen two brothers killed in military clashes, but that wasn’t his main reason for objecting. Polish independence in 1919 had been accompanied by a wave of anti-Jewish riots, pogroms, killing hundrds. Many of the worst clashes were prompted or carried out by Polish soldiers, always citing some unproven Jewish provocation.

My grandfather faced a gut-wrenching choice: whether to risk his life for a country that had given his people pogroms and oppression, or whether to leave his family’s centuries-old home and follow a wild scheme of underground flight across war-torn Europe, hoping eventually to reunite with wife and children in faraway Amerca.

Poland’s defense against Trotsky’s 1920 invasion would be brilliant and heroic. It would stand firm and defeat the Red Army in dramatic fashion in the Battle of Warsaw, deservedly remembered in Polish history as the “Miracle on the Vistula.” But by forcing my family to uproot itself and flee, it would save us from death in a far worse crisis just over the horizon, the Holocaust of World War II.

Create a free website or blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.